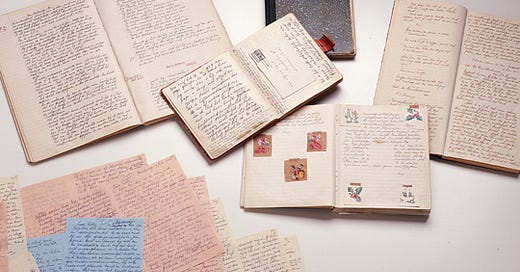

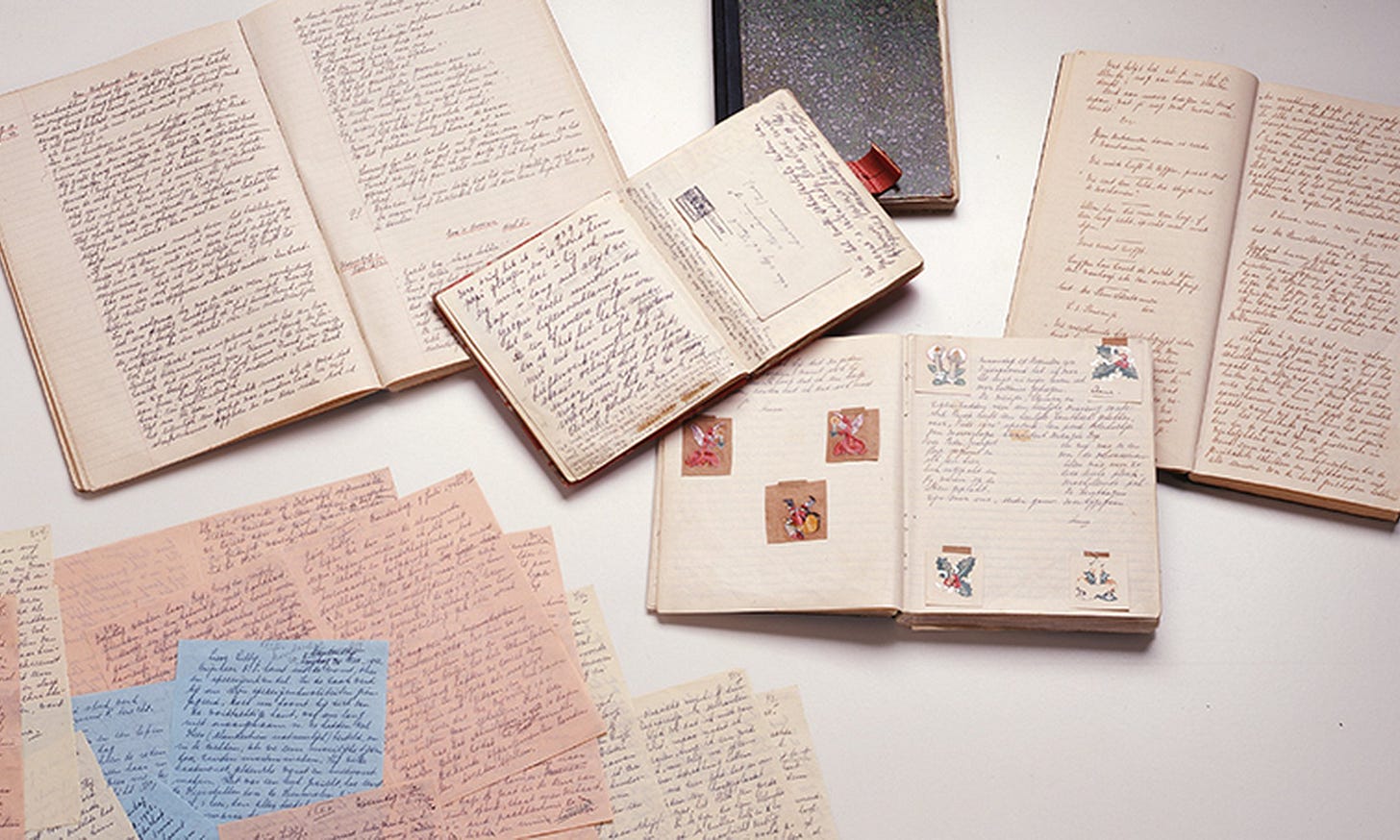

On her thirteenth birthday Anne Frank famously made a new friend, and she immediately wrote to this friend:

I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone, and I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support. (12 June 1942)

This friend was a diary, a birthday present of her own choosing. Anne wrote this entry while she and her Jewish family were hidden in confined quarters in Nazi-occuped Amsterdam, before her family was betrayed, and before she died in the Bergen-Belsen death camp less than three years later.

Writing down your experience can be more than a hobby, self-indulgence or even self-care. It can be breathing space and a way to survive. Anne said in her diary that “the nicest part is being able to write down all my thoughts and feelings; otherwise, I'd absolutely suffocate.” (16 March 1944)

Anne’s journalling gave her room to roam in her thoughts, outside of her daily challenges, and allowed her to connect with an idea of a world beyond her walls that was friendly and waiting to hear her voice. Writing helped bring her felt experience to the surface, and made her aware that she might be documenting this experience for a future post-war audience:

I really believe, Kits, that I'm slightly bats today, and yet I don't know why. Everything here is so mixed up, nothing's connected any more, and sometimes I very much doubt whether in the future anyone will be interested in all my tosh. "The unbosomings of an ugly duckling" will be the title of all this nonsense. My diary really won't be much use to Messrs. Bolkestein or Gerbrandy [members of the Dutch cabinet who had requested that people document their wartime experiences]. (14 April 1944)

Even given the ubiquity of tik-tok in mediating and unfolding real-time experience, there are many whose lives remain hidden to us, at least for the moment, but whose situation may later come to light through their written thoughts. Students who are part of immigrant families in the fashion district of Los Angeles, avoiding school and public places. Young people from Tehran, where bombs are falling, internet communication is down and the Woman, Life, Freedom movement is on pause. (But hoping to reignite: “We’re the embers under the smouldering ash; any day we could catch fire”, Anonymous). Their felt experience may emerge, eventually, through words on a page or screen, but for the moment these lives remain hidden from the wider world.

Writing, even from captivity, can save us from despair and can preserve our humor and sense of common humanity in grim circumstances. For Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition leader who died in a remote Siberian jail, writing in captivity was a way in which he could privately play out his sense of humour against the grim reality of surveillance and deprivation:

I’ve decided that I will, after all, keep a diary. First, because Oleg has given me some notebooks. Second, because it would be a shame to let such a fine magical date as 21.01.21 go to waste. And third, because if I don’t, some amusing goings-on will be forgotten.

As Navalny is taken to see a prison psychologist his writing falls into private whimsy about how he could scare people behind the mirror with a weird face, and he chortles that “if there are dudes behind the mirror, they must be thinking, This man is wrong in the head. He keeps writing things down and hooting with laughter.”

Writing in captivity is a way to preserve a sense of self and community and to tap into an innate human creativity. In No Friend but the Mountains Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani writes about being imprisoned on Manus Island for five years. Even in his isolated context, under constant surveillance, it was important for Boochani to write about his experience, to sing Parsi songs, to recite old verse and to compose words into new poetic arrangements. Why? Survival:

I have reached a good understanding of this situation: the only people who can overcome and survive all the suffering inflicted by the prison are those who exercise creativity. That is, those who can trave the outlines of hope using the melodic humming and visions from beyond the prison fences and the beehives we live in.

Writing can give humour and hope for survival in extreme situations, but words can also need to be wrestled with.

Ahmet Altan, a writer imprisoned by the Turkish government on trumped up charges of political terrorism, felt the strain of his own word-wrestle as he smuggled his memoirs out of prison via long phone texts. Altan laments in I Will Never See the World Again that:

It is impossible to describe the kind of longing one experiences in prison. It is so deep, so naked, so primal and no work can be that naked and primal. It is a feeling impossible to describe in words. It can only be described as the growling and moaning sounds of a dog that has been shot.

Writing can provide words or phrases that resonate with a felt experience, and carry the felt experience forward with meaning, but sometimes the words that are needed are elusive and mysterious. Like Altan’s prose, the words can evoke a sense of abject groaning rather than calm precision.

Eugene Gedlin, psychotherapist, thinks that it is best to pay attention to your bodily experience as you search for words to describe a felt experience. The process is tentative, cannot be forced, and might feel a bit weird:

When there is a felt sense, only certain phrases of actions will resonate with the felt sense and carry it forward. Until such phrases or action-steps come, we do not know what they will be. (Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy)

Altan’s image of a dog even brings his prison experience even out of a familiar human category, such is the intense strangeness of his sense of longing behind bars. Gedlin says that felt experiences are often very unfamiliar in their make-up:

“Even when we know a lot about what went into it, a felt sense includes much that is not known. It is the unique sense of a whole intricacy, and so it does not fall within a familiar category.”

The Bible’s New Testament tells us that God sometimes shares our inability to find the exact words to say about our experience, and that wordless groans can be just the right thing, even for God: “We do not know what we ought to pray for, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us through wordless groans.” (Romans 8:26)

I am writing here about writing; and also reaching towards an idea that writing words that resonate with our felt experience could be a form of prayer. Even if the exactly right words don’t come to the surface straight away, even if there is groaning and longing built into the experience of writing — this might be the very point at which we get divine guidance.

Each of us lives in a particular time and space, but could writing about our experiences within time and space be a prayerful portal into something divine, something unbounded, something eternally present within the world’s chaos?

As our words come, as they are shepherded into phrases and sentences, we might feel love. Love for ourselves, our histories, our communities; love for everything around us that we bring to our attention as we write and hope for a creative flow. A love that patiently chews and meditates on embodied experience in order to give it life on the page.